Finding Your Fiduciary Financial Advisor

When you are selecting or retaining a financial advisor, how do you know if you are making the best choice?

Why do we invest in stocks? Many of us do so because stocks offer higher expected returns than cash and short-term government debt, such as Treasury bills. This difference in expected returns between stocks and Treasury bills is called the equity premium. When investors evaluate an equity strategy, an important attribute to assess is the size of cash holdings. A higher allocation to cash means lower exposure to the equity premium—not a desirable outcome for investors pursuing higher expected returns.

A high allocation to cash and cash-like instruments, however, is not the only way in which an equity strategy can reduce its exposure to the equity premium. A less obvious culprit is cash exposure through holdings in companies that are the targets of cash mergers.

If the market expects that the acquisition will go through, the stock of the acquisition target becomes a source of cash that will flow to investors when the deal closes. Thus, when a firm becomes the target of a cash acquisition, its stock price generally moves toward the proposed acquisition price and stays there until the deal closes. Investors holding stock of companies that are the target of a cash acquisition may therefore have unintentional cash-like exposure, giving up the desired expected returns associated with an equity investment.

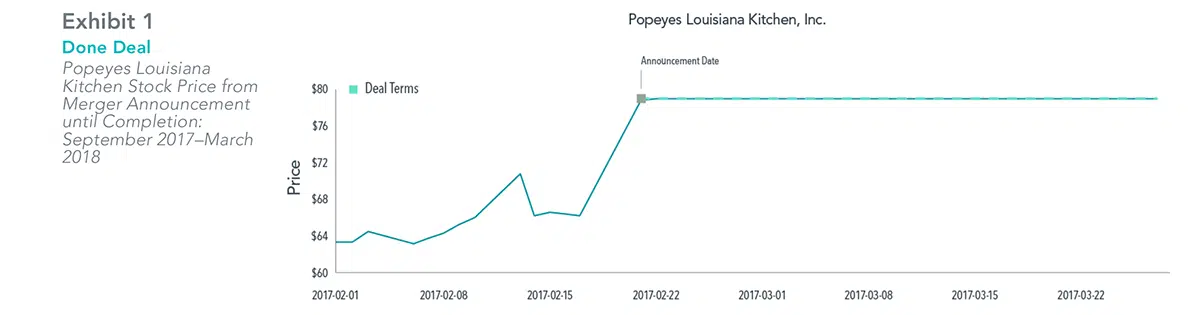

As seen in Exhibit 1, for example, Popeyes’s stock price remained fairly flat following the announcement date of an intended acquisition, staying within $0.06 of deal terms, until the acquisition was completed one month later.1

Past performance is not a guarantee of future results.

How often do we observe such cash mergers? Research by Dimensional shows that, from January 2011 through December 2018, more than 9,000 mergers were announced around the world, and most involved the acquiring firm offering cash to shareholders of the target firm. The majority of cash mergers targeted small cap stocks and were successfully completed. Did most result in unintentional cash-like exposure? We examine cash mergers of small caps in 11 countries over that period and confirm that stocks of companies that were the target of a cash acquisition tended to have cash-like returns following the deal announcement.2 This is particularly true for deals that were more likely to be completed, as suggested by the price of the merger target trading within a tight range of deal terms at least once.

Moreover, by holding merger targets to deal completion, investors give up some control on the timing of cash flows into the portfolio and may therefore be forced to demand immediacy in quickly deploying large cash flows when the deal completes. The concern is further exacerbated by the fact that cash mergers occur predominantly among small cap stocks, which tend to have higher trading costs.

Investors cannot control corporate actions, but they can plan for them. A systematic equity portfolio designed to efficiently and accurately target higher expected returns can incorporate information about corporate actions, including merger activity, every day. Through process-driven yet flexible implementation, small cap stocks that are the target of a cash acquisition and are trading very closely to deal terms can be systematically sold from the portfolio in a thoughtful manner without demanding immediacy from the marketplace. Thus, an approach that systematically divests of such merger targets reduces unintentional cash-like exposure while also maintaining control of the timing of cash flows. In essence, such an approach can pursue higher expected returns while managing risks and controlling costs.

FOOTNOTES

(1) Maggie McGrath, “A Whopper Of A Deal: Burger King Owner Restaurant Brands International Acquires Popeyes For $1.8 Billion,” Forbes, February 21, 2017.

(2) Kaitlin Simpson Hendrix, “Cash by Any Other Name” (white paper, Dimensional Fund Advisors, 2020)

This post was prepared and first distributed by Dimensional Fund Advisors.

Shore Point Advisors is registered as an investment adviser with the State of New Jersey. Shore Point Advisors only transacts business in states where it is properly registered, or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements. Past performance is not indicative of future returns. All investment strategies have the potential for profit or loss. There are no assurances that an investor’s portfolio will match or outperform any particular benchmark. Content was prepared by a third-party provider. All information is based on sources deemed reliable, but no warranty or guarantee is made as to its accuracy or completeness. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of the authors on the date of publication and are subject to change.

When you are selecting or retaining a financial advisor, how do you know if you are making the best choice?

Equity compensation can provide a big financial boost, but it is important to manage it by balancing potential risks and rewards.

In the second part of this young investor series, we discuss three more investment concepts every young investor may want to embrace.

If you are new to investing, it can be tough to know where to get started. There is so much information and advice out there.